NGS Portrait Gallery Before and After Coal 21sr March March 2024 Review

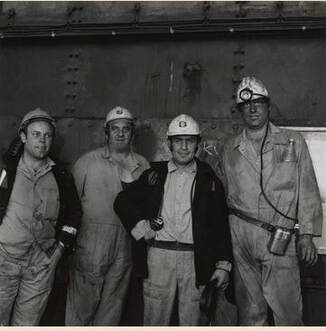

Photograph © Milton Rogovin

Before and After Coal Images and Voices from Scotland’s Mining Communities is at the Portrait Gallery (NGS Queen Street) until Sunday 15 September offering an insight into an industry and a way of life that has for the most part been lost forever, another footnote in the history books.

This exhibition is a collaborative work that stretches back in time whilst also connecting with people who may be the last first-hand witnesses of Scotland’s once great mining industry and its communities.

In 1982 American photographer Milton Rogovin came to Scotland to photograph Scottish miners at their pits, and more privately in their homes and during their leisure activities. Now over 40 years on from these photographs, artist Nicky Bird has updated the original documentation of miners from the 1980s by meeting with individuals and families who have a connection with the original photographs.

This new project which was initiated with a series of “Show and Tell” events across what was once the heartland of the Scottish mining industry has seen people from Fife, Ayrshire and the Lothians become involved in what was for many a voyage of rediscovery of family members and sometimes even the original miners and their families of forty years ago looking back through time at their own selves.

As we are told in the exhibition, Milton Rogovin was not given permission to document the miners working at the actual coal-face, and this is for me a problem as it means that we are unable to see just how dangerous and claustrophobic the daily working life of a coal miner could be.

What these photographs do give us though is an insight to miners at their pit on the working areas closer to ground level and above ground, and they still capture that spirit of men (there were no women working at the Scottish coal-face at this point in time) who knew that every person had to rely upon the other for their collective safety underground. If there were any disagreements between men, they had to be left above ground.

These photographs of miners and their families at home give us all some idea of how important family life was to everyone. Traditionally son would follow father into working in the mines, but many families also saw that a life for their children outside of the mines (if they wanted this) was also possible. This was a community where almost every man would be either a miner, or connected to the pits in some way or another, and the economic survival of not only the family home but also the whole community would depend greatly upon the pits for survival. What happened to these families and communities when the pits were closed and that income and way of life was gone would make a powerful follow up to this exhibition.

Leisure time to miners and the whole community was important and the focal point of much of this activity would be at one of the many miners’ working clubs across Scotland and it is perhaps here that some of the most interesting (for me) photographs are. Here we can see on some of the older miners just what a lifetime of hard manual work can do to a body, but still the smiles on so many of their faces show people who took great pride in that work and so much pleasure relaxing at a game of darts, or just a pint or two (or three) with friends and family.

In some ways there is always a feeling that this could all be a bit of a closed society, even a claustrophobic one, as everyone knew one another in their community and often shared that common bond of working in the same pit together. In other ways though, this was clearly a very open community, always willing to welcome any strangers into it with open arms, and the input to this exhibition from many mining communities, including Newtongrange, bears witness to this.

Had these photographs been taken even a few years later though they would have told a very different story as the Thatcher government brought the full weight of political power down upon miners across the country to both close many of the mines forever and break forever one of the strongest trade unions of the day. To do this a civilian police force was in all too many cases turned into a government militia and we should never bear witness to that abuse of political power and authority in this country again.

Review by Tom King © 2024

www.artsreviewsedinburgh.com

This exhibition is a collaborative work that stretches back in time whilst also connecting with people who may be the last first-hand witnesses of Scotland’s once great mining industry and its communities.

In 1982 American photographer Milton Rogovin came to Scotland to photograph Scottish miners at their pits, and more privately in their homes and during their leisure activities. Now over 40 years on from these photographs, artist Nicky Bird has updated the original documentation of miners from the 1980s by meeting with individuals and families who have a connection with the original photographs.

This new project which was initiated with a series of “Show and Tell” events across what was once the heartland of the Scottish mining industry has seen people from Fife, Ayrshire and the Lothians become involved in what was for many a voyage of rediscovery of family members and sometimes even the original miners and their families of forty years ago looking back through time at their own selves.

As we are told in the exhibition, Milton Rogovin was not given permission to document the miners working at the actual coal-face, and this is for me a problem as it means that we are unable to see just how dangerous and claustrophobic the daily working life of a coal miner could be.

What these photographs do give us though is an insight to miners at their pit on the working areas closer to ground level and above ground, and they still capture that spirit of men (there were no women working at the Scottish coal-face at this point in time) who knew that every person had to rely upon the other for their collective safety underground. If there were any disagreements between men, they had to be left above ground.

These photographs of miners and their families at home give us all some idea of how important family life was to everyone. Traditionally son would follow father into working in the mines, but many families also saw that a life for their children outside of the mines (if they wanted this) was also possible. This was a community where almost every man would be either a miner, or connected to the pits in some way or another, and the economic survival of not only the family home but also the whole community would depend greatly upon the pits for survival. What happened to these families and communities when the pits were closed and that income and way of life was gone would make a powerful follow up to this exhibition.

Leisure time to miners and the whole community was important and the focal point of much of this activity would be at one of the many miners’ working clubs across Scotland and it is perhaps here that some of the most interesting (for me) photographs are. Here we can see on some of the older miners just what a lifetime of hard manual work can do to a body, but still the smiles on so many of their faces show people who took great pride in that work and so much pleasure relaxing at a game of darts, or just a pint or two (or three) with friends and family.

In some ways there is always a feeling that this could all be a bit of a closed society, even a claustrophobic one, as everyone knew one another in their community and often shared that common bond of working in the same pit together. In other ways though, this was clearly a very open community, always willing to welcome any strangers into it with open arms, and the input to this exhibition from many mining communities, including Newtongrange, bears witness to this.

Had these photographs been taken even a few years later though they would have told a very different story as the Thatcher government brought the full weight of political power down upon miners across the country to both close many of the mines forever and break forever one of the strongest trade unions of the day. To do this a civilian police force was in all too many cases turned into a government militia and we should never bear witness to that abuse of political power and authority in this country again.

Review by Tom King © 2024

www.artsreviewsedinburgh.com